In my class Internet and the EU we have discusses the rapid changes in the global media landscape; two recent additions to Webster’s Dictionary are Podcast: noun a Web-based audio broadcast via an RSS feed accessed by subscription over the Internet and Blog: noun: an online diary; a personal chronological log of thoughts published on a Web page; also called Weblog*. These words point to the role of the internet at the beginning of the twenty first century and the significance of a New Media. But I want us to cast our minds back not merely as etymologists, but as linguistic archaeologists in the mould of Carter, and look at the colourful history of two words with interesting and very different origins, one coming from poor nineteenth century Ireland and the other from Classical Greece.

When I was growing up in the Nineteen Eighties South Africa was rarely out of the news. Nelson Mandela was still confined to his cell, and the cruel system of Apartheid separated Black and white, effectively ostracizing the black community in their own country. It was the wish of many countries around the world to in turn ostracize South Africa for its inherently barbaric system. South Africa was banned from many sporting events, Rock musicians vowed not to play Sun City and in a supermarket in Ireland young working class girls held industrial action and some were fired from their jobs as cashiers from the country’s largest retailer for refusing to sell South African oranges. In time the supermarket Dunne’s Stores gave into the young girls’ demands and South African oranges vanished from Irish shelves; until the end of Apartheid in 1994. South Africa was, before 1994, a pariah state, ostracized and shunned by the international community and there was a general boycott of South African goods.

From Africa we turn our attention north to Greece and back in time to the classical world. We are all aware of Athens as the seat of European democracy and civilisation and many of our political and legal institutions mirror those of ancient Greece. When an individual fell out of favour, or when someone was seen as a potential tyrant or troublemaker, citizens of Athens would gather and decide whether to ostracize that unlucky person. The meaning has altered down the years but effectively this was a peaceful process whereby the group would vote to exile the individual concerned for a period of ten years. Citizens voted for or against ostracism using small clay tablets called ostrakon. This was highly effective in pre-empting the rise of a tyrant or of solving conflicts without recourse to warfare.

South Africa during the years of Apartheid faced both ostracism and was the target of numerous boycotts. Boycotts have been used effectively as a non-violent method of resistance, Koreans being no strangers to this tactic. Some famous international examples of boycotts are; The May Fourth Movement, which began in China in 1919 and boycotted Japanese goods in protest at Japanese territorial gains from Germany at the Treaty of Versailles, the boycott of British goods by Indians led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1921 and the Boycott of countries, chiefly the USA and USSR, of the 1980 and 1984 Olympics for essentially cold war reasons.

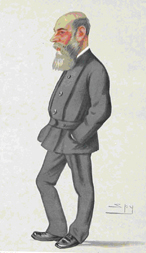

Another victim of the boycott was an English Captain from whom we get this word; none other than Captain Charles Boycott. Captain Boycott was a British landowner who controlled an estate of land in the West of Ireland in 1880. Boycott was among many British landowners who effectively stole the land from the local people and rented it back to them at exorbitant prices. The practice of high rent by the colonial landowners precipitated a land war in Ireland, where the native Irish attempted to regain the land that sustained them. This land war was to lead eventually to the removal of the British from Ireland in 1922.

Poor captain boycott must have felt all alone when all of his tenants simultaneously refused to talk to him, pay him rent, sit next to him in church, serve a drink or talk to him in the local pub and generally act as if he didn’t exist.. Boycott felt exasperated and called for help from British Loyalists in the North of Ireland. He managed to get a number of British soldiers to help him to harvest his potato crop, but the cost of bringing in extra labour was over ten times the value of the crop. Boycott faced financial ruin and was a social outcast, ostracised, and as the Times of London Reported in November 1880 “The people …have resolved to “Boycott them” and refused to sell them food or drink”. Needless to say all of this was too much for Captain Boycott and he left Ireland with his family in December of that year the first modern victim of the Boycott.

North Korea’s recent nuclear test has gotten a lot of attention and as I listen to podcasts and read Blogs about how North Korea has become increasingly ostracised in the international community and how they are effectively being boycotted by the US and Japan my attention turns to Captain Boycott and I wonder what he would make of the whole affair.

*Webster's New Millennium Dictionary of English

©Copyright 2006 Andrew Brennan

By Andrew Brennan

Prof., Dept. of European Studies

Prof., Dept. of European Studies